A practical guide to using narrative and storyboards to design products & experiences, and organize teams to deliver them

A Snow White Story

Over the 2011 holiday season, Airbnb co-founder Brian Chesky was looking for a way to concisely capture the customer experience. He had just finished a biography on Walt Disney and how the Disney company developed the storyboard to capture the vision for their most ambitious production to-date: Snow White. Following Disney’s example, Airbnb hired former Pixar animator Nick Sung to capture the company’s primary user journey in just 15 frames as a storyboard. Whereas previous efforts had mapped the UX of the website, these frames captured the offline experience of the customer.

The storyboard aligned their company purpose and vision. Articulating the concept visually led to an explosion of creativity in problem solving, and recognition of how to reduce previously hidden offline frictions for their customers. The results were transformative and catalyzed the most aggressive period of growth in Airbnb’s history.

In May 2015, the New York Times Magazine published a brilliant article, What Hollywood Can Teach Us About the Future of Work. In it, the author is surprised by the 150 highly skilled contractors who show up and get to work without stepping on each other’s toes:

…there was no transition time; everybody worked together seamlessly, instantly. The set designer told me about the shade of off-white that he chose for the walls, how it supported the feel of the scene. The costume designer had agonized over precisely which sandals the lead actor should wear. They told me all this, but they didn’t need to tell one another. They just got to work, and somehow it all fit together.

Storyboarding has long been a tool of experienced digital user experience designers. Outside of Airbnb, experience designers are vastly underutilized by the broader organization. Nathan Blecharczyk, co-founder and CTO of Airbnb, reveals they are used to answer product and organizational questions:

The storyboard was a galvanizing event in the company. We all now know what “frames” of the customer experience we are working to better serve. Everyone from customer service to our executive team gets shown the storyboard when they first join and it’s integral to how we make product and organizational decisions. Whenever there’s a question about what should be a priority, we ask ourselves which frame will this product or idea serve. It’s a litmus test for all the possible opportunities and a focusing mechanism for the company.

In fact, of Airbnb’s original 15 frames mapping the guest journey, only one of the frames illustrate the online experience.

A Guide to Storytelling

The above anecdote may be inspiring, but it’s so much more useful to see how to apply it in practice. I’d like to introduce you to a fictitious startup — one audaciously silly and plausible — called You’re In, Inc. If you like the business enough to start it, consider including me as an advisor.

You’re In is a startup in the fashion of the Uberization of everything, allowing business owners to safely list their restrooms available for use by You’re In members. In addition to increased foot-traffic, business owners receive compensation each time their restroom is used, as well as data on the cleanliness and supply levels of their facilities.

To bring an organization to life, one must answer these fundamental questions:

- Why do we exist?

- Who do we serve?

- How do we serve them?

- Who do we need and how do they operate?

- How do we track our progress toward our purpose?

Purpose and Principles: Why We Exist

Every organization exists to realize its purpose. Google exists to organize the world’s information. Tesla’s is helping expedite the move from a mine-and-burn hydrocarbon economy towards a solar electric economy. You’re In believes everybody deserves a safe and clean bathroom.

A purpose emanates from principles shared among its inventors and founders. Principles, in the style of designer and thinker Bret Victor, are the foundational beliefs compelling an organization to act. Articulating an organization’s purpose and principles explicitly, as written statements, has profound and lasting effects: the principles act as the final arbiter for which actions an organization will and will not pursue.

Here are You’re In’s purpose and principles:

The purpose pulls the story forward.

Who We Serve: Casting Our Customers

The characters in our story are the customers and stakeholders who are served by the organization. Our customers should be realistic and reachable with the resources we have on hand, not overly aspirational: when producing your first movie, it’s unlikely you’ll be able to cast Al Pacino.

People do not act randomly. Their days are not determined by a dice roll. They are driven by their habits and motivations. When these habits and motivations intersect with an opportunity, they act. Business is understanding a person’s habits and motivations and presenting them with a mutually beneficial opportunity at the right time.

To cast our customers, we’ll write a short character biography for each major customer type our organization will serve. Designers call a character biography a persona. As in James Bond, many actors are capable of playing the part. In our business, many, many people are capable of playing the part of our customer. The information in our persona will allow us to find, reach, and serve an actual person. Just as the character biography for James Bond allowed the filmmakers to find Sean Connery. A good persona is detailed enough to act on, but not so wide that it could be just anybody. When in doubt, go narrow and expand your description over time.

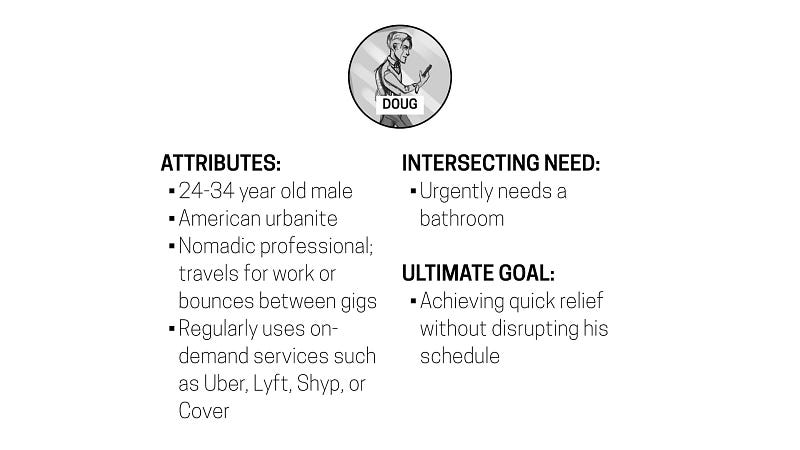

At a minimum, a persona should contain a name, descriptive attributes (such as age, sex, beliefs, and habits), the intersecting initial need our business serves, and their ultimate goal achieved by resolving their need.

When naming your persona, don’t use a segment description such as “millennial” or “youthful urbanite”. They need to feel like flesh and blood. If they’re young and from the Midwest, call them “Madison.” If they are middle-aged financial executives from Connecticut call them “Chip.” Asking yourself, “what does Madison want here?” enables you and your team to make real design decisions.

Here we’ve completed two personas for You’re In. Jenn represents a typical business owner in an American city who can provide You’re In with a supply of underutilized restrooms. The other, Doug, describes our on-the-go traveler who’d like to use them:

How We Serve Them: The Storyboard

Now we’re ready to take our characters on a journey. We’ll write the script for our personas: from the first time they heard of our organization, through their first interaction with us, to the moments that inspired loyalty, and finally to the moments that lead to them referring others to give us a try.

Our script won’t be a Choose Your Own Adventure. There won’t be any branches. It’s not a flowchart. Instead our script will be linear, an idealized journey aiding our persona in their pursuit toward their ultimate goal.

The prose doesn’t have to read well. The words are a means to creating a storyboard. We’ll be creating up to 15 or so different moments. Each moment is comprised of the following:

- The context — Where are they? How are they feeling? What do they need?

- The action — What action do they want to take? What action do they want to avoid?

- The outcome — What will result?

This framing is called a Job Story by Alan Klement. Its elegance lies in forcing you to make choices about your assumptions and empathize with your customer. By chaining these empathetic moments together you create an end-to-end experience for your customer to follow. Remember: organizations exist to provide purposeful experiences, not simply products.

The pattern for expressing a Job Story is given as follows:

When <situation or context>,

They want to <take action motivated by context>,

So that <outcome results>.

Let’s write out an idealized journey for Doug, our customer for You’re In using the Job Stories framework:

- When Doug is walking his neighborhood and sees You’re In brand collateral or attends his local farmer’s market and encounters You’re In event outreach staff, he wants to remember the app and its function, so that he can ease a future travel experience.

- When Doug is traveling and is in between appointments and feels the urge to use a restroom, he wants to remember the app and download it, so that he can try it and find a place to quickly relieve himself.

- When Doug opens the app the first time, he wants to understand the app quickly and find the nearest restroom, so that he can walk to where he can use the restroom.

- When Doug enters Jenn’s shop, he wants to minimally interact with shop staff and enter the restroom, so that he can get to the bathroom quickly without hassle.

- When Doug is in the bathroom the app presents him a star-rating interface to rate bathroom cleanliness and supply levels. He is educated that he’ll receive a surprise reward; he wants to input the information, so that he can find out the mystery behind his reward and receive it.

- When Doug inputs his star-ratings the connected vending machine dispenses an individually wrapped mint, he wants to take it, so that he can eat it or show his friends the novelty.

- When Doug needs a restroom again, he wants to quickly know which restrooms are around him, so that he can relieve himself without hassle.

- When Doug receives an email sometime later about his first experience and is offered an invitation to his friends in exchange for free use, he wants to invite his friend Mary, so that he receives his “free pee” credit.

If you can draw, you’re now in a good position to begin sketching your script as a sequence of storyboard frames. As you work, you’ll be startled by how many more choices you’ll need to be made to sketch out your user journey. With each choice will come additional clarity.

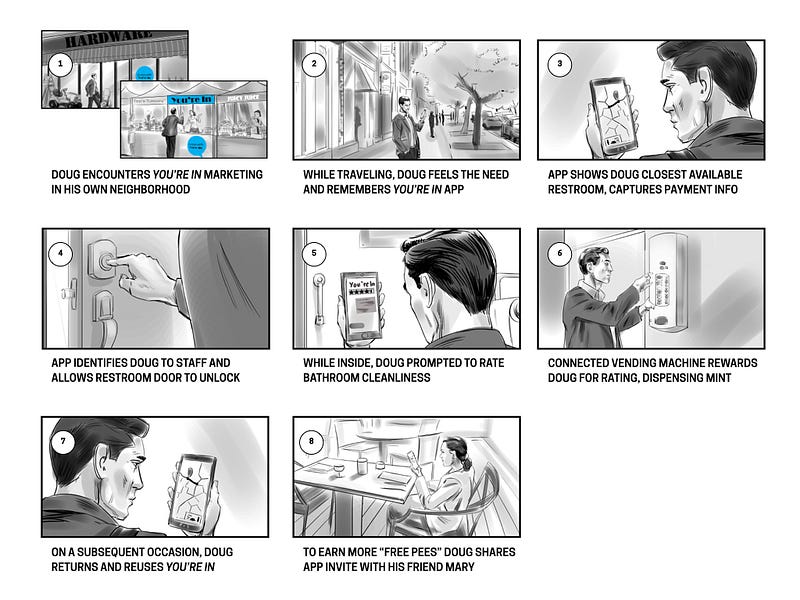

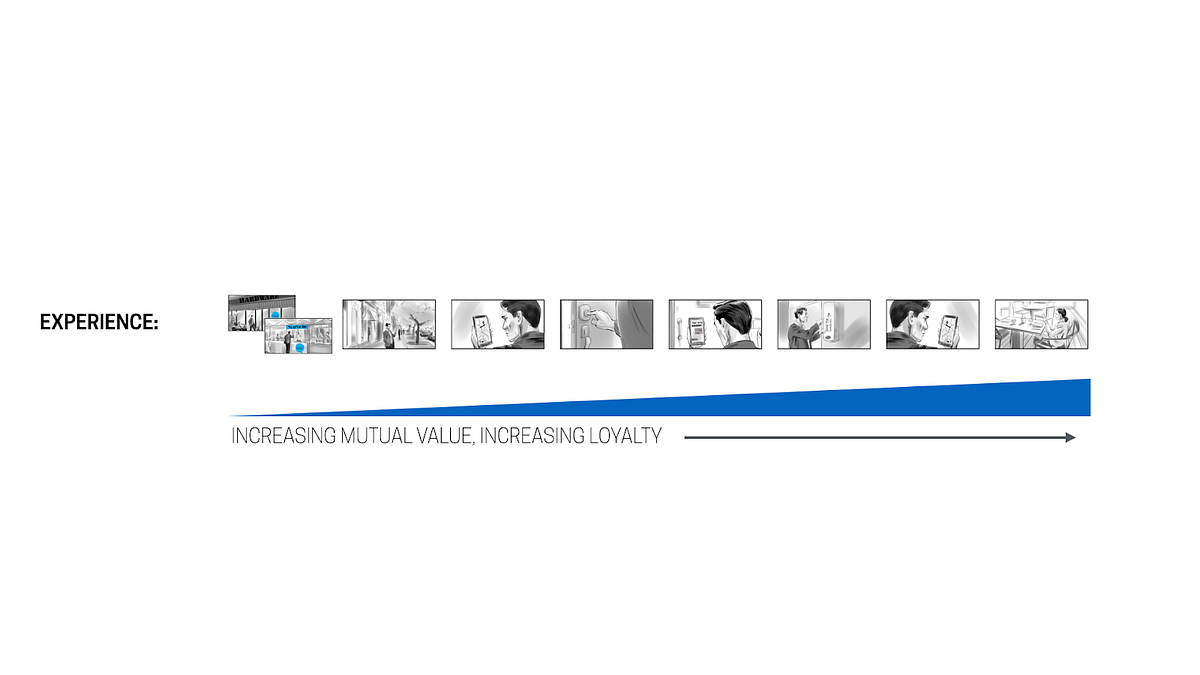

Here’s our rendered storyboard for the Job Stories above:

It’s beginning to feel real, isn’t it? Real enough where you can use these artifacts with actual users and build confidence in your value proposition.

If you can’t sketch, don’t panic. I can’t either. Even stick figures or art from The Noun Project will be effective. If you want full fidelity (and I recommend it!) there is an inexpensive hack: hire a storyboard artist from Fiverr. I’ll admit to you now, that’s what I did above. The storyboard for Doug was drawn by Fiverr user conceptart09.

I’ve found if you transform your Job Stories into a simple screenplay, it gives storyboard artists all they need to work. To create a screenplay, all you’ll need to provide is an aesthetic description of your personas as characters and a scene-by-scene description of your frames. Each scene should contain a scene heading (interior, exterior, and environment) with camera direction (close-up, medium wide, or wide shot and primary subject). As an example, here’s an except of the first two scenes from the storyboard of Doug:

CHARACTERS

DOUG: a 30-something professional. He travels for work. He can be seen about town with his shoulder bag.

SCENES

SCENE 1

EXT. MEDIUM WIDE CITY STREET IN FRONT OF ENTRANCE TO HARDWARE STORE — DAY

Doug walks by Hardware store, sees sticker on door that reads “Go Here with You’re In.” Sticker image similar to below

SCENE 2

EXT. WIDE SHOT FARMER’S MARKET ON CLOSED CITY STREETS — DAY

Street is lined with booths at a weekend farmer’s market.Three booths are visible: the first is partially out of frame and its banner shows it sells “Juicy Juice.” Set similar to below, but camera angle pointing more directly at booths.

Structuring your customer’s journey as a linear story arc enables you to use it in some surprisingly useful ways. The storyboard provides a spine from which you can hang your organization’s potential efforts and measure your progress toward your organization’s purpose. Let’s see how it can be used to figure out what to bring to market.

Defining Your Initial Product Experience

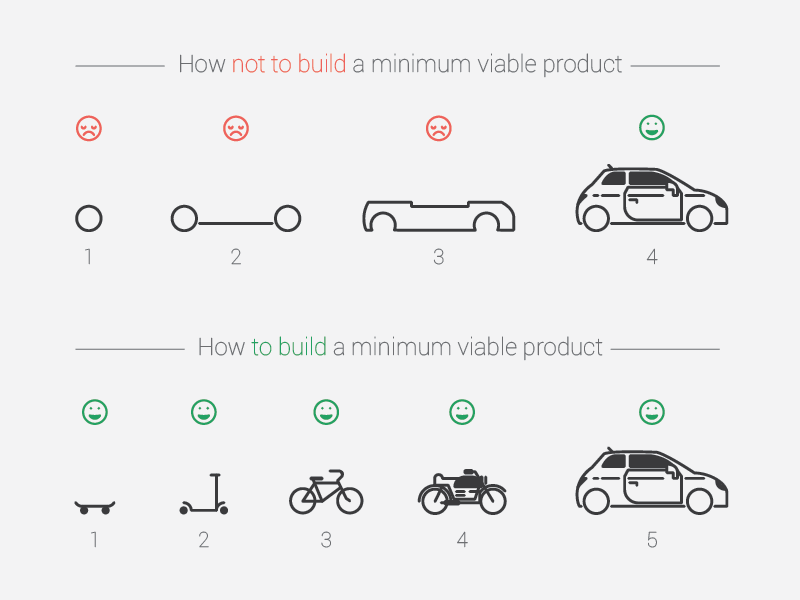

Organizing your efforts along a storyboard allows you to quickly ship a complete experience for your customers. You may be familiar with the following diagram from How Spotify Builds Products:

Without a persona’s complete experience mapped out as a storyboard, it’s difficult to judge if what you might build is just a feature (a single wheel) or a minimum viable product (a skateboard). To define your initial product, write down solutions you could provide under each storyboard frame. By selecting a set of experiences that cover the entire story arc — Bingo! — you’ve defined a complete experience.

When generating solutions, sympathize with your customer’s persona in the context of the storyboard frame. Act out the scene if necessary. Resist the urge to ask, “what would I want?” and instead ask, “what would my customer want in this situation?” Remember that a lot of solutions need not be technical as much of the experience may be taking place offline.

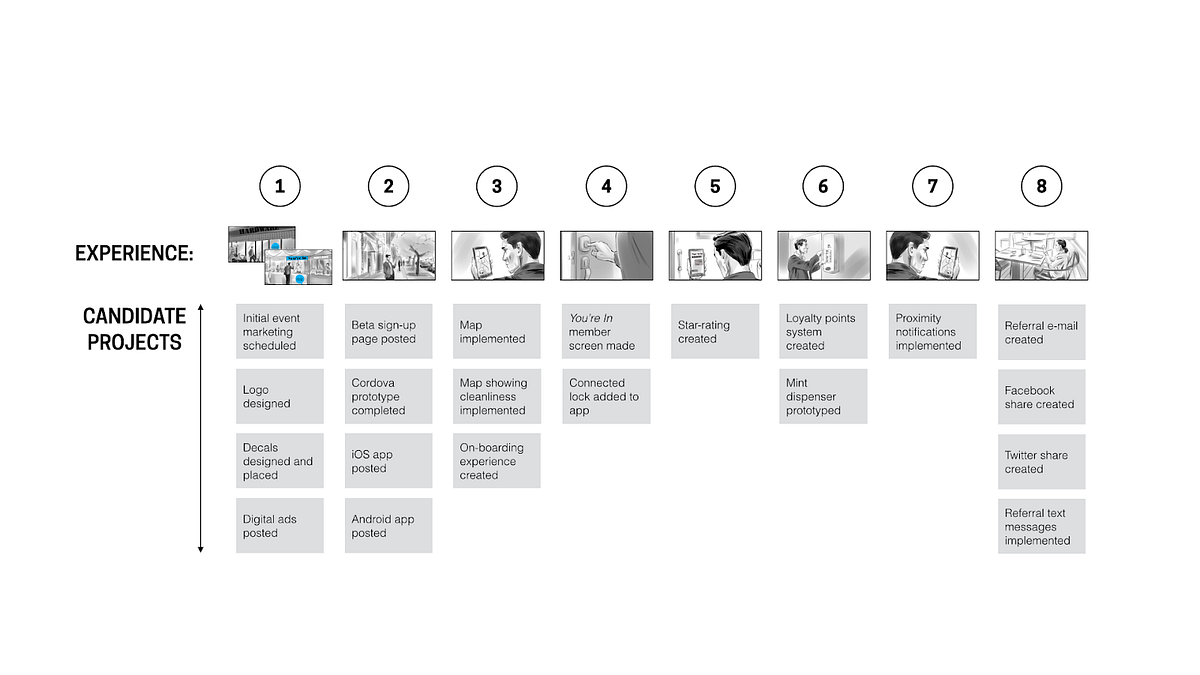

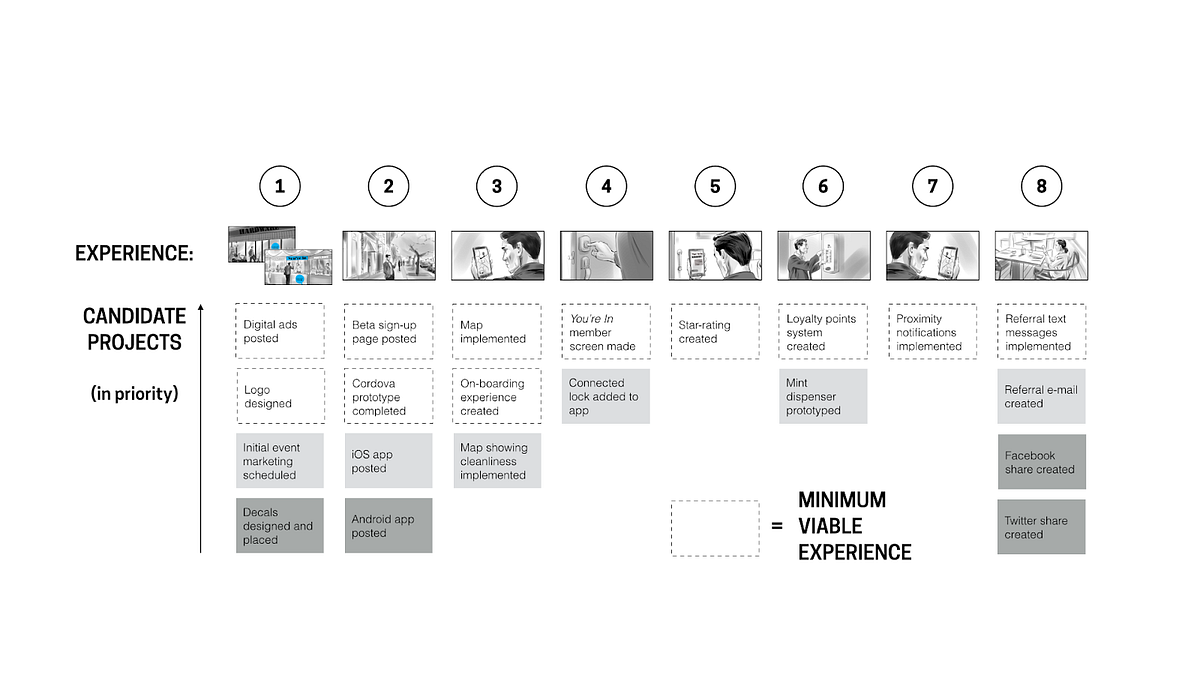

Let’s have a look at a limited set of solutions for Doug’s journey through You’re In:

Not all of these potential solutions are equal to one another in effort or return. If a solution is too risky to build–but the potential reward great–that’s a clue to divide it into smaller parts or test it with potential customers that match your persona.

To determine what we should begin building, we need to sort and filter these solutions by what we can do and what our customers might want us to do. I’m a fan of the Weighted Shortest Job First method popular among some Agile circles. What method you choose is up to you. What’s important is each frame of the customer journey is somehow addressed to create a complete experience.

After applying a hypothetical sort, let’s see what we should deliver:

The boxes with a dashed outline indicate what we should build first. The others are deferred, and we might build them later. Each prioritized project becomes a mission for an individual or a team to deliver.

Who We Need: Allocating Your Team

If you haven’t hired a team, having missions prioritized against a storyboard gives you insight into whom you’ll need to help build your products and operate your company. Continuing with our example persona and storyboards from You’re In, let’s see how we’d form teams.

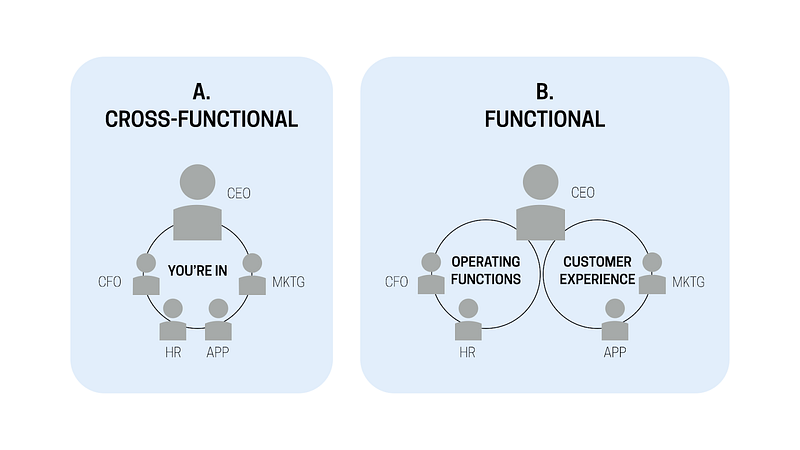

The storyboards we’ve generated for the company for Doug (above) are at the highest level in the organization’s hierarchy. They serve the company’s purpose directly. Meaning, the performance of their customer journeys should be under the purview of company leadership. One could imagine either of the following structures:

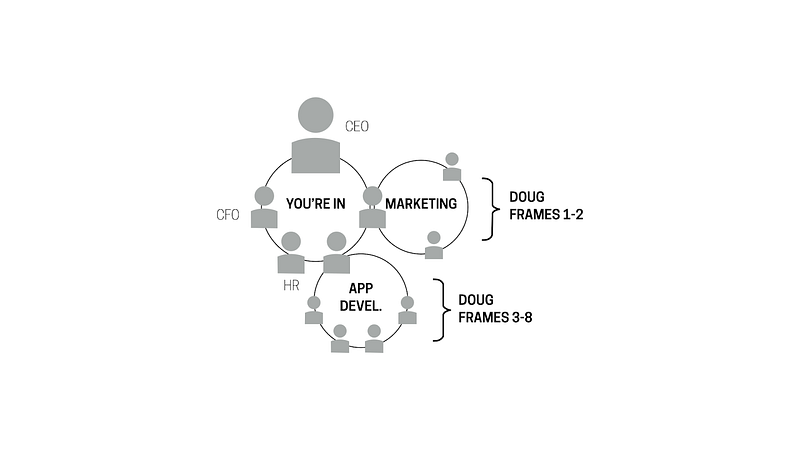

In both (A) the cross-functional structure and (B) the more functional structure, the CEO acts as “Chief Product Officer” prioritizing and allocating company resources toward fulfilling the You’re In customer experience. The choice between electing (A) and (B) depends largely on who needs to communicate with whom to produce our customer’s journey. Here again, the storyboard is a great tool. For each project the CEO asks, “who can lead a team to tackle project X?” Within You’re In it’s clear some of the projects require marketing and communications capabilities, for others they are clearly in an application design and engineering domain. Let’s see an example of how this exchange might shake out:

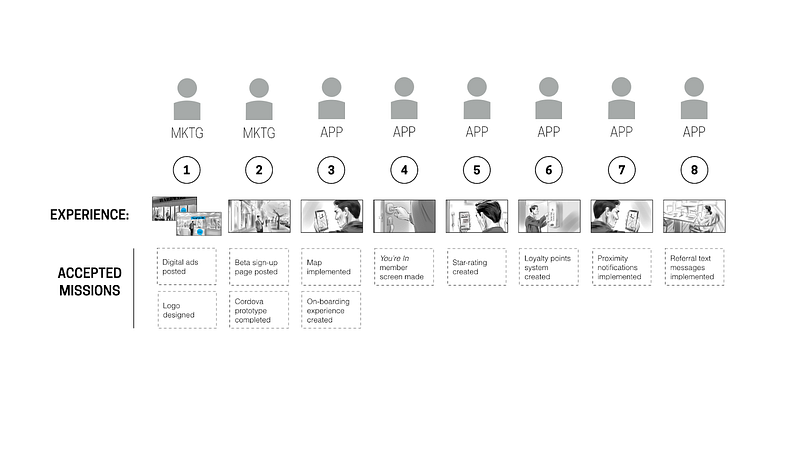

Above, two leaders divided the storyboard. Next, each leader would ask themselves for each frame, “who do I need to help me?” If the company resources required are the same between two frames, then they belong to the same team. For example, if the individuals producing Frame 3 are the same as Frames 4–8, then these frames can be owned by a single team with a single leader. However, if they are different there is nothing preventing a leader from owning two separate teams. For example, Frame 2 could be owned by a blended team of marketing and technical resources.

Using our storyboard, the following team structure emerges:

At first glance, the advantage of starting from a storyboard to drive team formation might not be clear. The teams bringing You’re In to life don’t look any different than an entrepreneur might otherwise premeditated. The difference lies within the explicit purpose afforded by the pictures within the frames of the storyboard: the mission isn’t to simply be a developer or be a marketer but to resolve frames to experiences that exist in reality and work to continuously improve upon them.

Doing the Work

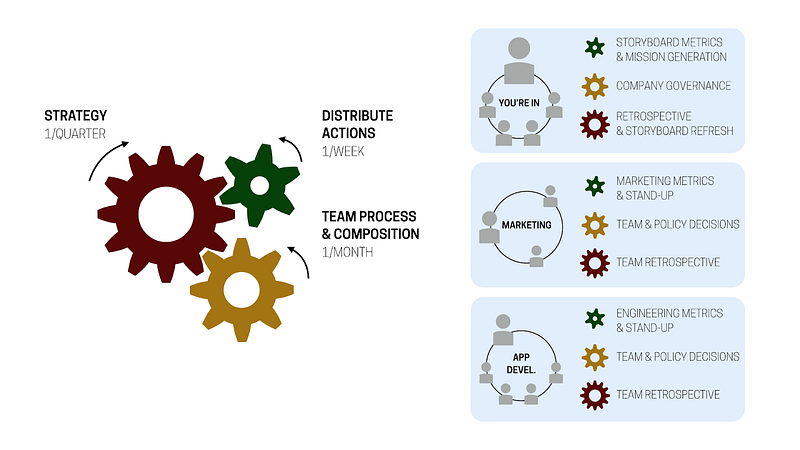

It’s vital that a team and the broader organization be able to respond to new information as it’s encountered. Each team must have an cadence for taking care of 3 needs: distributing work, modifying the team, and refining the strategy. Let’s see how this would play out for the three teams of You’re In:

The team should spend most of its time pursing its most important mission, breaking it down into tasks that can be shared by its team members. Occasionally team members should meet with an intent to improve the way they work together — using a tool like my very own Parabol. And less frequently still, a team must retreat and consider fundamental strategic change. Change can happen top-down (new purpose, customers, and storyboards) or bottom-up (we change the feature, the team, or provide data to revise the story, customers, or purpose).

These rhythms require our team be furnished with good data. We must know what data to measure. The storyboard can help here, too.

Tracking Progress: How We Measure

Up to this point, we’ve used storyboards to help us define a set of experiences for the customers we wish to serve. Once the journey is defined and the product shipped, it becomes a theory for how customers interact with our organization. Examining Doug’s storyboards for You’re In, you’ll note as Doug-type customers progress through the journey there is an increasing exchange of value between Doug and our organization. You’ll also notice that by the end of the journey, Doug has become a regular user of You’re In’s products and chosen to share them with his friend Mary. Doug has become loyal.

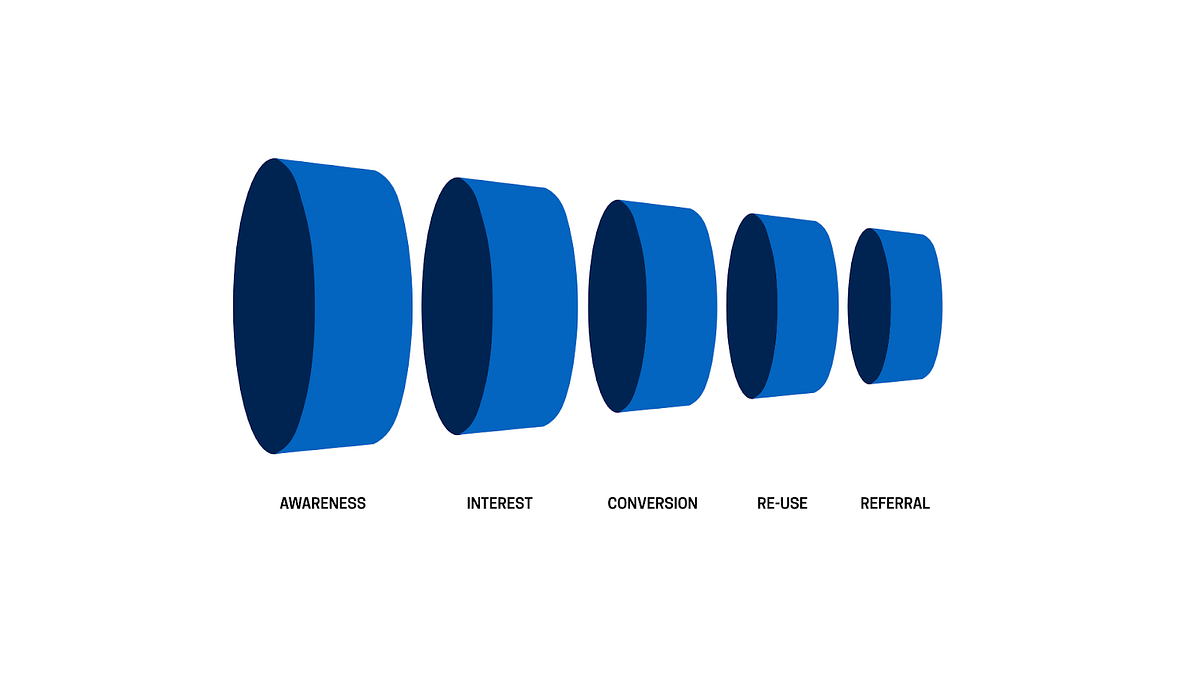

An organization will rarely survive on a single customer. You’re In will depend on finding as many people matching Doug’s profile as it can and converting them to loyal, paying customers. An abstract tool called a marketing funnel has provided organizations insight into the performance of relationships with potential and active customers. The funnel divides the relationship an individual can have with a business into stages of increasing loyalty.

At the entry point of the funnel you have the entire potential market — in the case of You’re In, all the people in the world that match Doug’s profile. You then measure how many customers become aware of your services (for example, how many clicked through on an ad), how many became interested (e.g. spent time on the website), and so on until they are loyal and telling all their friends.

The funnel is a powerful concept. Looking at transitions between funnel stages you can tell where you need to invest next. A product owner’s job could be described as increasing throughput through the funnel by reducing friction and removing blockages. It automatically answers the question: do I spend more on advertising or on product features? The numbers will tell you.

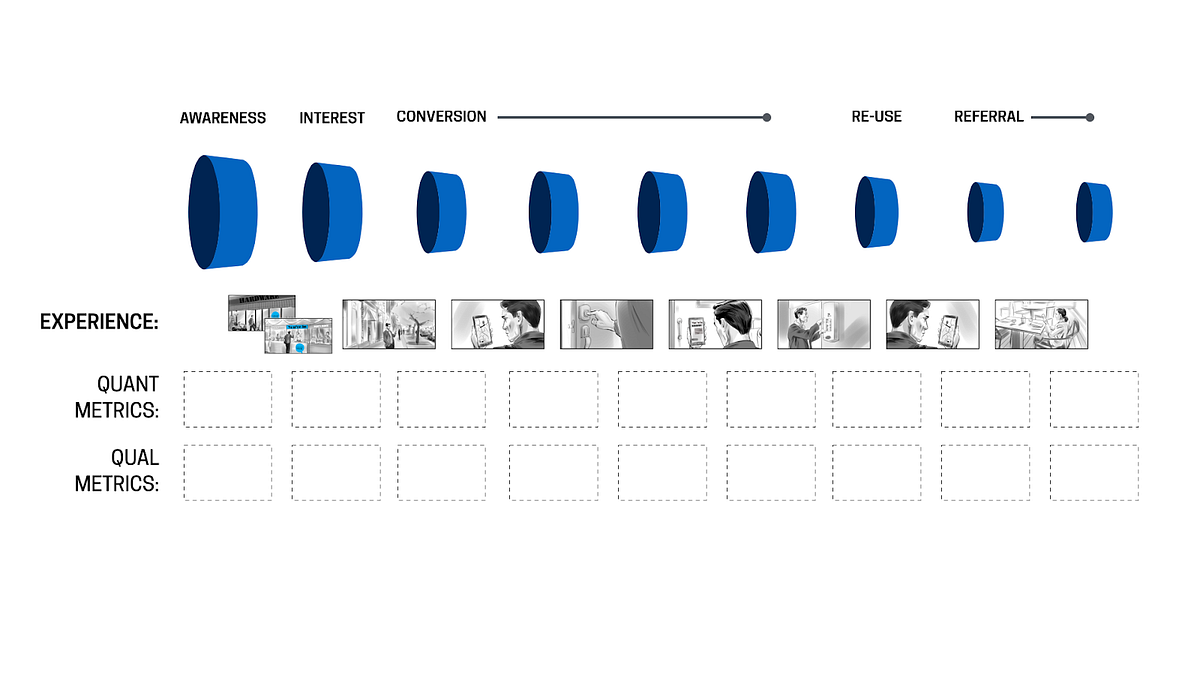

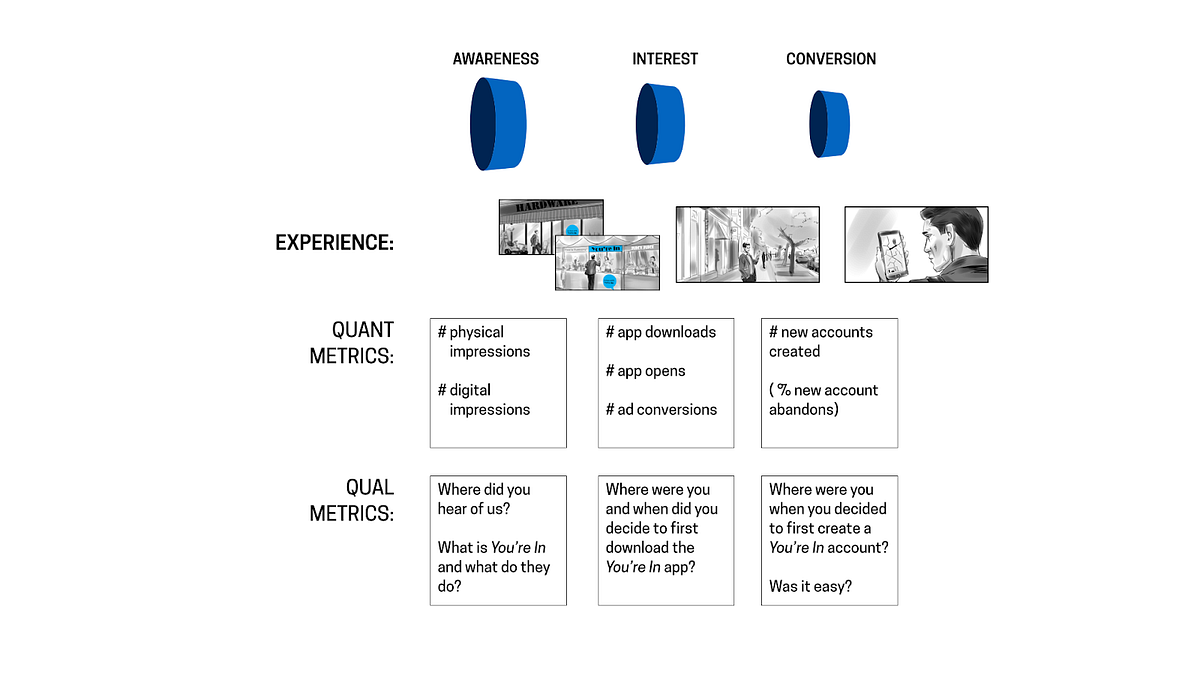

Mapping a storyboard to a marketing funnel is easy, simply write the funnel stage above the appropriate storyboard frame. If a funnel stage belongs to more than one frame, repeat it.

The spaces between the frames are our points of measurement. Below the frames we’ll create a set of blank spaces for capturing quantitative and qualitative metrics. The idea is to sense important metrics for when an individual crosses from one storyboard frame to another and why and how they did it. Building a quantitative and a qualitative picture for our users gives us the data we need to continuously reduce friction.

Consider the very first quantitative metric. How do we measure when Doug crosses the threshold from Unaware to Aware–making it to the first storyboard frame. We can measure the number of decals we’ve hung around the city. We can measure the number of people we’ve spoken to at events. We can measure the number of digital ad impressions and their click-through rate.

Qualitatively we can randomly target and ask individuals why they stopped to talk to us at an event. We can ask why they clicked on the ad. We can find out what they expected us to provide for them. The answers to these questions will help us sharpen our targeting.

Let’s see an example of the first few funnel stages completed with metrics:

Tracking these metrics over time starts to build trends you can act upon. In many cases, you can build a model to directly estimate how many individuals are at each stage. In the above example, the number of new accounts created is a very good proxy for the number of users you will have at the conversion stage.

Labeling all of your storyboards with funnel stages allows you to roll up the data into one super-funnel encapsulating the performance of the entire organization. One dashboard to rule them all.

Data to Fuel Iteration

Measurement is nothing without a list of hypotheses. Ask yourself:

How do we expect each metric to perform? Over what time period?

Build it. Launch it. Measure it. Then, iterate. If you get stuck, move from micro to macro: first ask, are we failing to make this moment magical? Next, is this the wrong experience for our persona? Then, is our understanding of the persona incorrect? And finally, should we be serving somebody else entirely?

I started writing this guide in January of 2016. It took until April of 2019 for me to hit the publish button. A fellow entrepreneur asked for advice mapping customer journeys and I told him, “I drafted this piece I can share…” Consider it the first iteration…